By Jane Duncan Rogers for Next Avenue

My husband was diagnosed with cancer in 2010. We managed to focus on the positive side of things (the doctors said that if they got all the cancer out of his stomach in an operation, then his prognosis was quite good.) But we blithely ignored the statistics which were not on our side. I think this is probably called denial.

We couldn’t, however, deny the situation any longer in the face of a conversation with the surgeon just after the operation. We had approached this appointment gratefully, as we’d been told all the cancer had been removed. But we had a shock.

“A wide margin was taken out around the source of the cancer, but the biopsy has shown minute traces of it elsewhere,” he explained. “I can’t recommend another operation. Your body will not be able to stand it.”

“So, what do we do?” I asked, bluntly.

“Go home, recover as best as possible, and you will be able to buy some time with more chemotherapy,” the surgeon said.

He must have known that Philip’s chances of survival had suddenly changed from 50/50, down to about 5 percent. We didn’t, though.

Or at least if we did, we also did what you can only do when someone is here, alive, if not kicking — we got on with living as best we could.

Important Questions to Answer

Because that’s the thing. You really are alive right up until the moment when you are not. Despite the fact that death can come suddenly, many people have a long, slow trajectory these days. Philip’s demise was in-between; it took 14 months from diagnosis until his actual death. In every one of the moments in the trajectory, that person is alive. Possibly with not much quality of life, but alive all the same.

Philip’s quality of life was fine, though, for a few weeks. You wouldn’t have known he was seriously ill until he began to find difficulty in swallowing.

During this time, I received an email from a close friend. She was asking a long list of questions of us both, but mainly for Philip. I knew he wouldn’t want to answer these; they were things like “Do you want to be buried or cremated?” “Does your partner know your user names and passwords?” and “Who would you like around you as you die?”

For me, the questions were about topics including: find out what the car needs, how any appliances work and what to do about a specific legal situation. Eventually, one Saturday morning, we tackled them.

Our Last Project Together

Poor Philip — for a man afraid of dying (which he was), this was an amazing act of courage, another step in the acceptance of what was happening. We began at the beginning, and continued on until the end, noticing that we were actually enjoying it. How strange!

In those two hours, I asked him the questions, and he gave me his answers. There were all kinds, from the most basic such as “What kind of coffin do you want?” to which he replied, “Any old box will do,” to more sensitive ones such as “Are there any of your personal items you would like to leave to anyone in particular?” This one we discussed in much more detail. It was tough; these are difficult questions to ask of somebody who knows he is going to be dying sooner rather than later.

The strange thing is, we not only felt a great sense of achievement afterwards, we were very close, connected and loving for the rest of that weekend. Who would have thought that? Despite the subject being his death, we ended up having a couple of hours of slightly macabre enjoyment together. Later, we referred to that time as our last project together.

Little did I know at the time, those answers were to be both a lifeline and a turning point for me.

I felt so good when the funeral director asked me what to dress the body in, and I could say confidently, “His dressing gown.” I would never have thought of dressing him in that, but I had made it for him, he had really loved it and so I was able to attend to that, knowing I was carrying out his wishes, which gave me some comfort in a really ghastly time.

I began to be grateful for what has become a cherished memory of our Saturday morning questioning session, as poignant and tender as it was.

Suggestions for Starting the Conversation

But he was reluctant, more than me, to address these subjects. So how do you actually start a conversation like this when someone is dying? Or even just an abstract conversation about death? Neither are easy in a society where talking about the “D” word is almost taboo.

Here are a few hints from my own experience, and what I have learned since then:

Create a context. At the time of writing this article, Aretha Franklin has just died without leaving a will, which (given the size of her estate) is going to cause a lot of problems. It would be entirely normal to ask your loved one “Have you got a will?” or “Aretha Franklin’s funeral arrangements are making me think about what I’d like. What would you want to do?” Generally, an open-ended question will work best if you want to discover information.

Create a structure. That’s what my questions did. Know in advance what you want to ask, or where you want to go with the conversation. Think about where you might have that conversation — alongside each other, without eye contact, might be best. It’s not very often that we are recommended NOT to have eye contact, but this is one case where it might apply.

Think about the words you might use. How do you actually start the conversation – and keep it going? The following starting points are helpful.

- Since ___ died, I’ve been thinking about life and death a lot. How do you feel about it?

- What do you think happens after you die?

- Do you know what you want for your funeral?

- I have some legal matters to sort out, and I need to find a power of attorney. Would you be willing to talk about this with me?

- I need to think about my future and I also need someone to help me just talk it through. Would you be willing to do that?

- Are there any particular milestones you would like to meet? (Examples might include an 80th birthday or a grandchild’s graduation. This is especially useful if the person is terminally ill.)

Most importantly, being prepared will help you become more at ease with this subject, and that in turn will transfer to the other person. Once you have begun this kind of talk, it can easily be continued at other relevant opportunities. You might even be surprised, as we were, at how it can bring relief and connection.

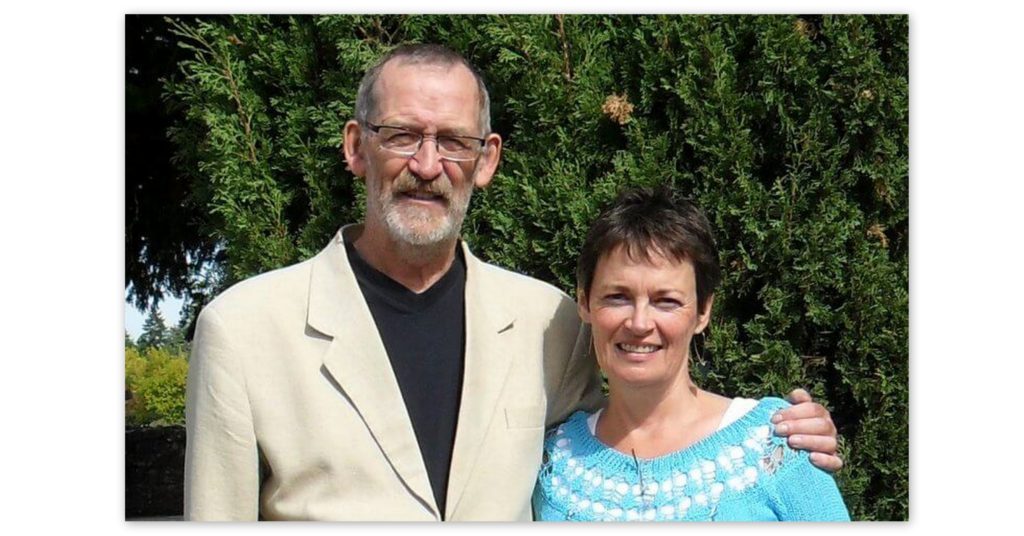

PHOTO: Jane and Phillip, courtesy of Jane Duncan Rogers