Credit: Adobe

By Richard Eisenberg for Next Avenue

Leaving a legacy — sounds like something only wealthy people can do, right? Like making a giant bequest to a university or passing on a significant estate to your children. Actually, though, a new Bank of America Merrill Lynch/Age Wave survey and the new book by Canadian sociologist and researcher Lyndsay Green, The Well Lived-Life: Live With Purpose and Be Remembered, suggest that leaving a legacy is not necessarily about money.

“We are all leaving a legacy, whether we like it or not,” said Green. “Our legacy is a combination of the way we live every day and the impact it has on our friends, our family, our community and the world, as well as how we prepare others for life without us. Leaving a legacy is a way to let others appreciate our love and our consideration for them because we took the time to plan ahead for the impact our absence would have on them.”

Nicely put, I think. And Green’s book provides plenty of smart, thoughtful, easy ways to leave a legacy for your loved ones — a personal legacy and a financial one.

For the latest in its excellent series of life-stage reports, Leaving a Legacy: A Lasting Gift to Loved Ones, Bank of America Merrill Lynch/Age Wave surveyed more than 3,000 adults (2,600 of them 55 and older) and conducted focus groups about end-of-life planning and leaving a legacy. Some of the results were disconcerting, surprising and even uplifting.

Here are a few of them, along with views about the findings from Age Wave founder and CEO Ken Dychtwald and Kevin Hindman, national trust executive for Bank of America Merrill Lynch, plus views from Green:

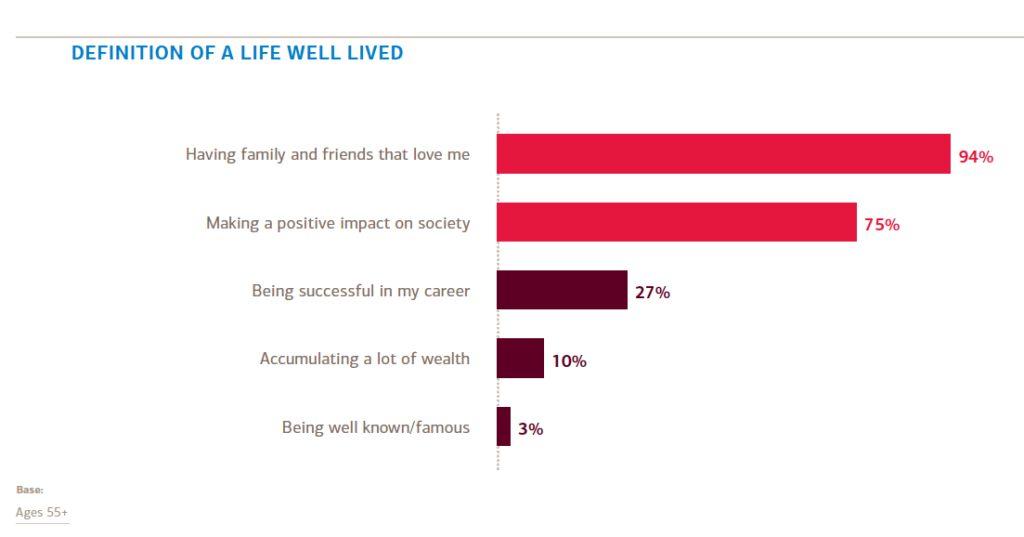

The public’s definition of a “life well lived” is more about love and less about lucre. A full 94 percent of survey respondents said the definition of a life well lived is “having friends and family that love me.” That was followed by 75 percent who said it’s about “having made a positive impact on society.” Only 10 percent said a life well lived is defined by “accumulating a lot of wealth.”

In the survey, Dychtwald said, “we saw a lot of people reflecting on who is the version of themselves that people will think of in their remaining years or after they’re gone. It wasn’t about the number of Instagram followers they had.”

When Green was researching her book, she was given a legacy exercise: “Imagine life ended abruptly right now and tomorrow would be a world with me. What responsibilities and commitments would be left dangling? And what messes — concrete and emotional — would I want to have sorted out?”

After she told people she interviewed about this exercise, some changed their lives to leave the legacy they wished. One woman repaired a rift with her brother. Some people started volunteering more. Others gave more money away. Some wrote wills or updated the ones they had. Some started writing memoirs.

“A lot realized their extended family had no idea of their broader family history that would die with them and wanted others to know their roots or, for their immediate family members, the choices they made in life and why they made them,” said Green.

People want to be remembered for how they lived, not what they did at work or how much money they amassed. A striking 69 percent of survey respondents said they most want to be remembered for “the memories I’ve shared with my loved ones.” By contrast, only 9 percent said “career success” and a puny 4 percent said “accumulated wealth.” Incidentally, these views were pretty consistent among respondents at all income levels.

If you’re in your 50s or 60s, it’s not too late to work on “becoming the person you want people to most remember,” Dychtwald said. Recently, he sat down with his grown daughter, took out a digital recorder and told her some stories about his life. “Most of it she had never heard and she so appreciated it,” he noted. “She thanked me for the gift. You know, leaving a legacy doesn’t have to be just ‘here’s how I want my funeral to proceed.’ We’d all do well if we told more of our stories.”

Recently, Dychtwald also digitized films of his daughter and son when they were children so they could relive sweet family memories.

For help on learning how to write a memoir that helps pass along what you believe in and the story of your life, read the Next Avenue article “How to Craft Your Memoir” and The Artist’s Way author Julia Cameron’s advice in “How to Figure Out ‘What Should I Do Next?’” You could also sign up for a memoir-writing class or use an online memoir writing platform like JamBios.

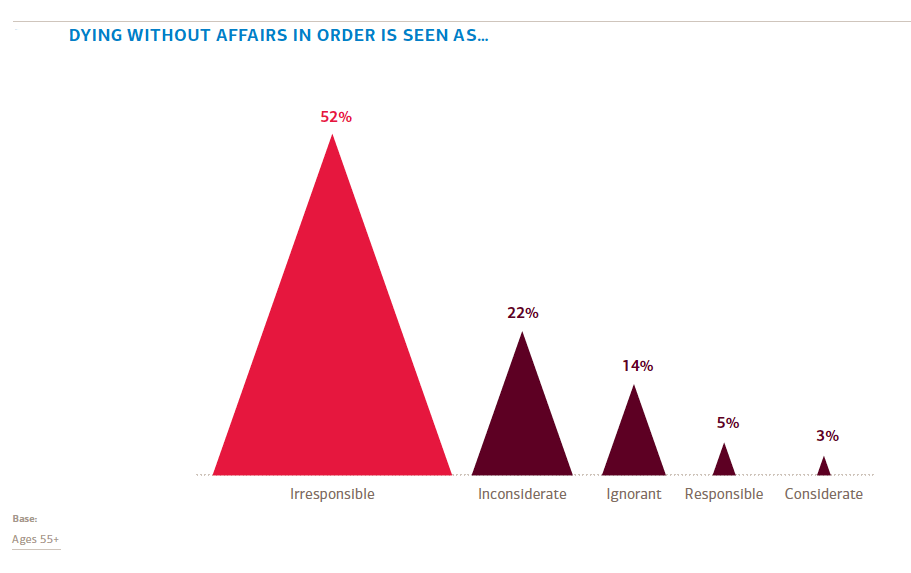

Although people 55+ know they need to get their affairs in order, many haven’t done so. Just 55 percent of the survey respondents age 55 and older have a will. Worse, a mere 18 percent have what Bank of America Merrill Lynch calls the three essential documents for legacy planning: a will, a health care directive (specifying end-of-life preferences and designating someone to make health decisions for you if you can’t) and a durable power of attorney (designating someone to make financial and legacy-related decisions for you if you can’t).

“Part of it is just a lack of understanding about how to get started,” said Hindman. He suggests talking with family and friends and sharing your end-of-life planning intentions with them.

Also, added Hindman, “talk to a financial adviser to help set out the steps you need to take. It’s not just having the three documents, it’s also about being sure your financial accounts are titled correctly, your beneficiary designations are up to date and family members can access this information electronically with your passwords.”

A lack of preparation could be the undoing of the hoped-for legacy for people lacking wills and key estate planning documents. As Green told me, “If we live stellar lives, we can tarnish our legacy by leaving our affairs in a mess and forcing others to clean up after us when we’re gone.”

Worst of all, it could “lead to a very disorganized, difficult and expensive problem to resolve at the worst possible time — when family members are grieving,” said Hindman. “Without proper planning about how an estate will be distributed, family members can land in court.”

If you don’t have a will and haven’t given your loved ones vital information about where your financial accounts are and your passwords, “the very people you want to remember you as a wonderful person may wind up saying something like: ‘Dad was a great guy, but what a mess he left,’” said Dychtwald.

Why do so many people know what they need to do to leave a legacy but fail to do it? “We have not institutionalized thoughtful planning and consideration for things that might happen in our lives,” said Dychtwald. “As a result, we’re not comfortable with doing it.”

Parents age 55+ had surprising views about when to leave an inheritance and who should get how much of their estate. Only 36 percent of boomers surveyed and 44 percent of Gen Xers said “it is a parent’s duty to leave their children some type of inheritance.” (But a much higher percentage of their kids’ generation — 55 percent of Millennials surveyed — felt that way.)

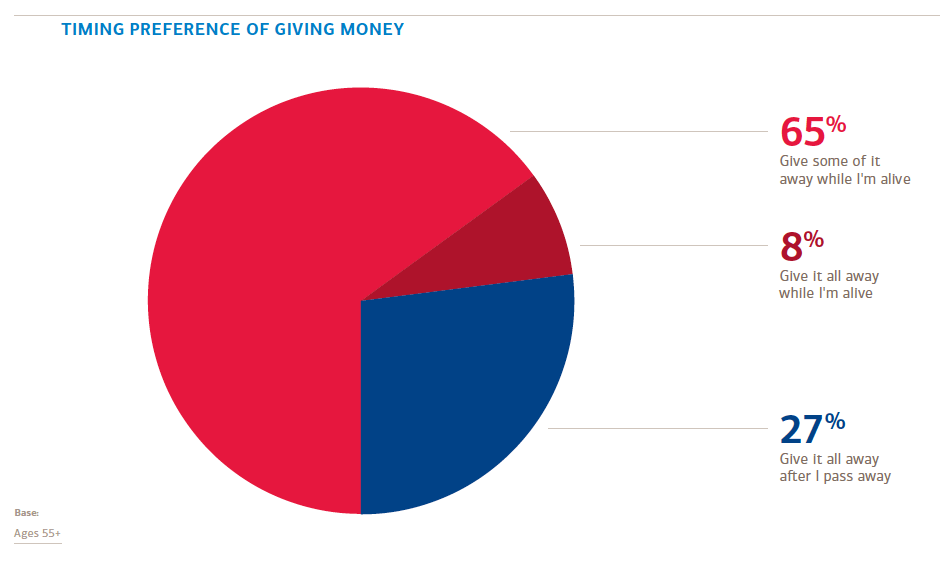

And a stunning 65 percent of people 55 and older said they’d prefer to give some of their money away while they’re still alive; 8 percent favored giving it all away before they die. Just 27 percent wanted to give all their money away after they pass away. “A lot of the respondents said: ‘Why wait?’” Hindman noted. “Why not share some of the wealth today, at a time when the children can really use it?”

The children and grandchildren might need cash now to buy a house or to pay for college. Help them out and “then you get to enjoy the benefit of seeing smiles on their faces and being appreciated for your gift,” said Dychtwald.

Caregiving is playing an interesting role in inheritances, too, the survey found. Two-thirds of respondents 55 and older said they feel children who cared for them in their later years should get a larger share of the financial pie than those who didn’t. “There was a strong reaction that for children who are more caring and helpful, that should be reflected in what they receive,” Dychtwald said.

Green recommends parents incorporate their children in their charitable giving plans. “You’ll be surprised how interested they become in that,” she said. “They can help research charities and build that into a family donation for a family legacy.”

Dychtwald believes the idea of leaving a legacy is something you think more about as you get older.

“For young people, so much of life is about going forward — what do you want to make of yourself?,” he said. “There comes a point in life when you start to think: ‘What do I wish I had made of myself? Did I, or did I not, achieve my goals and turn out to be the person I wanted to be?’”

Green’s parting thought: “People say, ‘I don’t have time to leave a legacy.’ I say, ‘No, your legacy is everything you’re doing. It’s immersed in every single action and day. Just be more conscious that you are living fully and that you are fully engaged and are making an impact. Take it seriously.”

Richard Eisenberg is the Senior Web Editor of the Money & Security and Work & Purpose channels of Next Avenue and Managing Editor for the site. He is the author of How to Avoid a Mid-Life Financial Crisis and has been a personal finance editor at Money, Yahoo, Good Housekeeping, and CBS MoneyWatch.