By Patricia Corrigan for Next Avenue

How we process grief and loss is highly personal. Some retreat from the world for a while. Some throw themselves into work. Still others turn to artistic expression to ease their pain. “After a traumatic loss, the arts allow what can’t be spoken about to come into form,” says Sharon Strouse. She knows what she’s talking about.

Strouse, 69, is a licensed clinical art therapist in Portland, Maine. In her private practice, through presentations nationwide and as associate director for the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition, she has helped thousands of individuals cope with grief. She focuses on traumatic loss, including suicide bereavement, Gold Star families (those who have lost a loved one who was serving in the military) and parents who have lost a child.

Her work is not just theoretical. Strouse lost her 17-year-old daughter to suicide almost two decades ago. As Strouse struggled to heal, she called on her professional skills to help her cope. “Ironically, I had never dealt with art therapy in personal exploration,” she says.

‘Creative Energy Makes You Still’

Strouse and her husband met with a psychiatrist, went to couples’ counseling and attended bereavement groups for about a year. But she felt little relief from the crushing sadness.

“My life was turned upside down — my identity as a human being, a wife, a mother and an art therapist,” she recalls. “One night, I was looking to God, saying ‘Help me.’ A little voice inside of me said to make a collage. I turned a light on in the kitchen, gathered magazines and art paper and I began.”

“My life was turned upside down — my identity as a human being, a wife, a mother and an art therapist,” she recalls. “One night, I was looking to God, saying ‘Help me.’ A little voice inside of me said to make a collage. I turned a light on in the kitchen, gathered magazines and art paper and I began.”

Strouse sat quietly with the thought that her daughter had died by suicide. Paging through the magazines, she looked for images and words that resonated with her. Then, using torn pieces of paper that reflected her fragmented emotional state to express her intense grief, Strouse crafted an abstract collage.

“The experience was life changing,” she says. “One of the compelling aspects of the creative process is that when you create in the moment, even when you go into a trauma to do it, creative energy makes you still. There is no suffering around it. I was able to sleep for the first time in a year.”

Strouse continued to make collages, working on some of them for a month or more. “At the time, I had no idea that was I doing would become a template for my current work,” she says.

Images of some of the collages are on her Artful Grief website. About a decade after her initial discovery, Strouse wrote Artful Grief: A Diary of Healing, a book that details her transformative healing through collage.

‘Through Dance, My Body and My Subconscious Spoke’

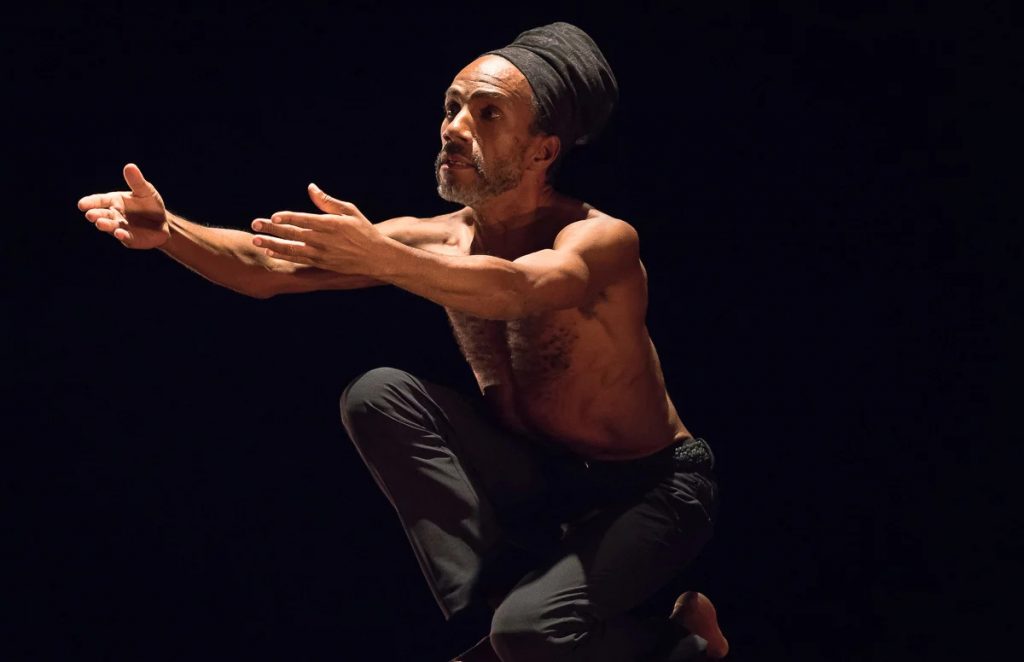

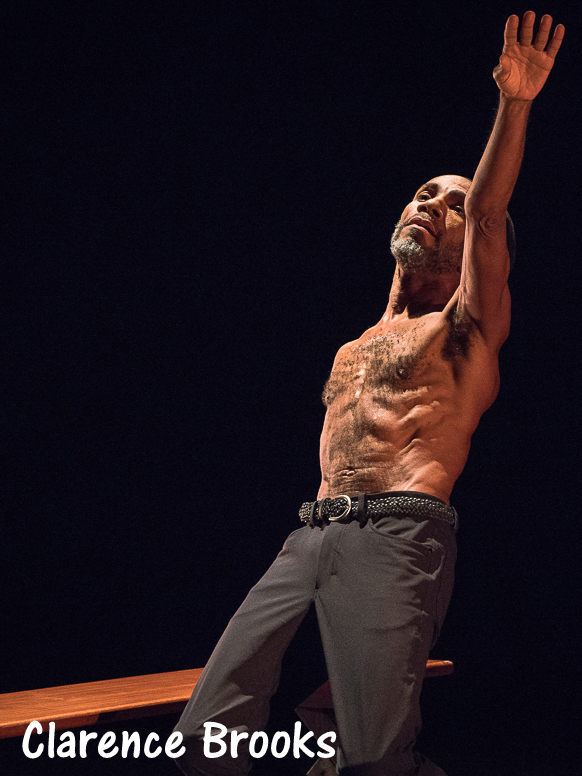

When Clarence Brooks lost a sister to brain cancer, he expressed his pain through dance, though he was not aware of that at the time.

Brooks, 59, is an associate professor and director of dance in the department of theater and dance at Florida Atlantic University (FAU) in Boca Raton, Fla. He produces and directs student showcases and performs in and directs the university’s professional dance company. Brooks also has performed with more than 60 American companies and toured throughout the U.S., Europe and Asia.

“Dance helped me navigate the loss of my sister,” he says. “As the oldest of four, I’ve always been the protector, and I could not protect any of us from this. I was completely beside myself.”

When he told his co-workers at the university his sad news, the director suggested Brooks spend some time at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, a nonprofit artists’ community in New Smyrna Beach, Fla. Soon after his sister’s funeral in 2004, Brooks headed there for a three-week dance residency.

“I didn’t tell anyone at the Center that I was grieving because I didn’t want them to be concerned about my well-being,” Brooks recalls. “I just went in the dance studio every day and started creating movement, nothing with a specific narrative.”

The following year, he taught some of the piece to graduate students at FAU. One student commented that the choreography brought to mind somebody dealing with a loss.

“That stopped me in my tracks,” Brooks says. “I thought I was in a different space with the piece, but the truth came out. We can’t hide from what our hearts, minds and souls are going through. Through dance, my body and my subconscious spoke.”

He adds, “I do find that being in the arts is cathartic, a way in which we can process our range of emotions and experiences.”

Performing While Grieving Is ‘an Out-of-Body Experience’

Music is where Stephen Winter sought solace when his stepfather, the man who raised him, died in 1994 after a car accident.

“When Ross passed, I was obliterated emotionally,” Winter says. “My instinct was to write something or play something, to help me to pull myself together. I wrote a lot of instrumental stuff to cope with his loss, including a Pink Floyd-like track called ‘Ciao, Baby.’ That’s something he always said.”

“When Ross passed, I was obliterated emotionally,” Winter says. “My instinct was to write something or play something, to help me to pull myself together. I wrote a lot of instrumental stuff to cope with his loss, including a Pink Floyd-like track called ‘Ciao, Baby.’ That’s something he always said.”

A keyboardist, vocalist and entertainer based in St. Louis, Winter, 59, has performed all over the world for the past 35 years. He plays “dueling piano” gigs, sings solo at pop events and sits in with bands.

Soon after playing piano at his stepfather’s memorial service, Winter had a professional commitment.

“Though everybody told me to take time off, I knew I had to go in to work,” Winter says. “I couldn’t sit at home thinking about it — that would have magnified the loss. So maybe I did sit sobbing in the parking lot first, but when I went on at 9 p.m., I put on my stage smile.”

In the years since his stepfather’s death, Winter has relied on the same strategy in the wake of other traumatic events, including the unexpected passing of dear friends, his own health problems and divorce.

“Under those circumstances, getting up there to perform is an out-of-body experience,” he says. “There have been times when afterward, I’ve been very proud of myself for holding it together while on stage.”

That’s what professional entertainers do, Winter says, because they must.

“I play and sing to make people happy, to reach people,” he says. “I’m on stage to help people get away from their problems, and if they have a good time, then I feel better, no matter what’s going on with me. That keeps me going.”

PHOTO at the very top: Clarence Brooks, associate professor and director of dance at Florida Atlantic University [Photo Credit: Stephen Pisano Photography]

Part of the VITALITY ARTS SPECIAL REPORT

Patricia Corrigan is a professional journalist, with decades of experience as a reporter and columnist at a metropolitan daily newspaper, and a book author. She now enjoys a lively freelance career, writing for numerous print and on-line publications. Read more from Patricia on her blog.