By Julie Pfitzinger for Next Avenue

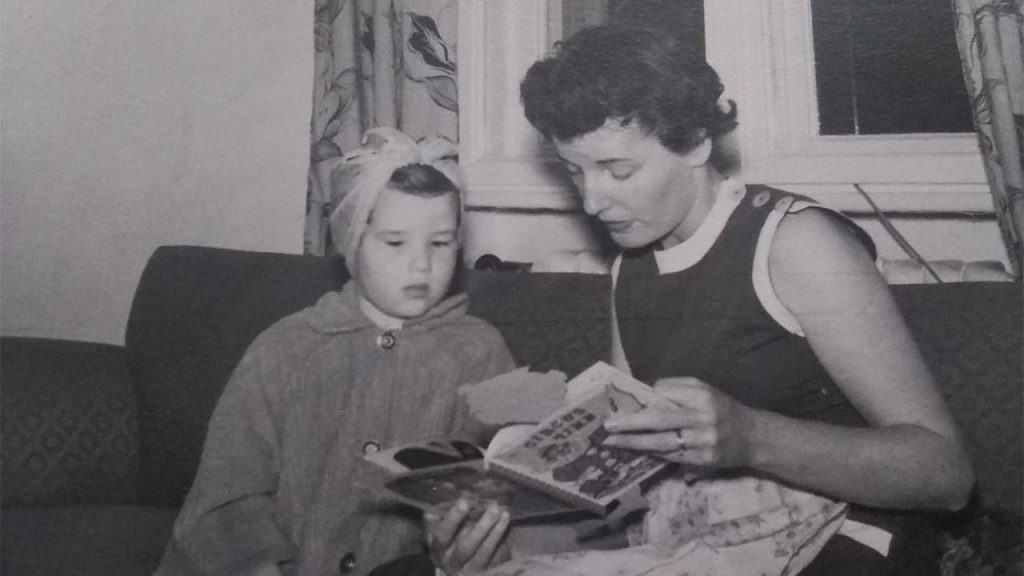

Fans of Elizabeth Berg’s novels know the loving care she takes in telling the stories of her characters, detailing the nuances of their lives and tenderly handling their struggles and sadness: Everything from “Open House,” an Oprah Book Club pick in 2000, to the 2017 novel “The Story of Arthur Truluv” are just two examples of many.

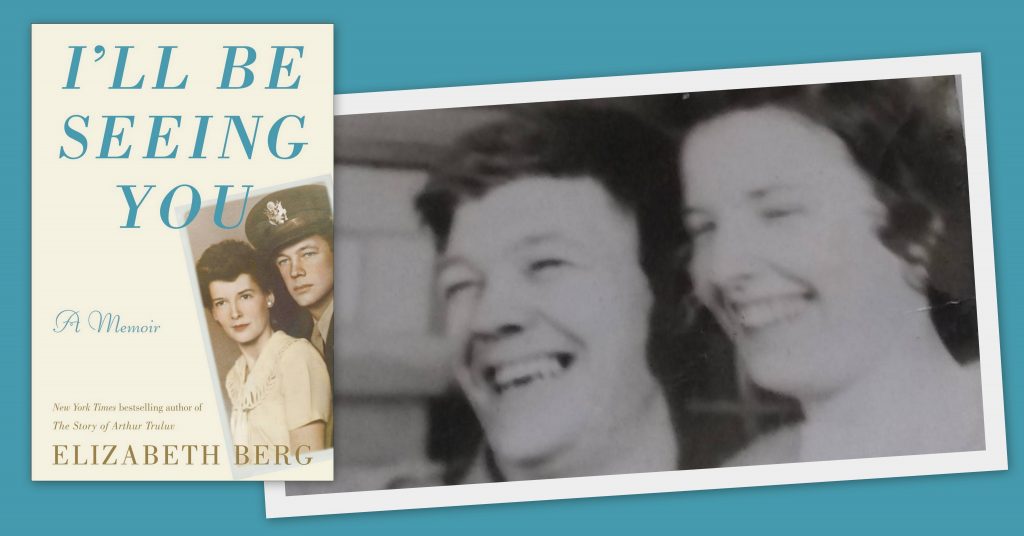

It is this same care that Berg, 71, brings to the almost-70-year love story of her own parents, Art and Jeanne Hoff, in her latest book, a memoir, called “I’ll Be Seeing You.”

It’s a love story that persists in the face of Art’s Alzheimer’s disease; an initially unhappy move from their beloved St. Paul, Minn. home into an assisted living facility, the cumulative effect of Art’s declining health; and Jeanne’s anger at her loss of autonomy, all happening alongside Berg’s own candid discoveries about growing older.

“If you’re of a certain age, you see what’s ahead for you, too,” Berg said in a recent interview. “[My parents] modeled behavior I’d like to not do, and what I’d like to do. I hope I learned something that will help my own children.”

Or as she writes in the prologue of the book, “So when I consider the story of my parents’ failing, I am picking up stones on the path to put into my pocket.”

A Profoundly Emotional Time

“I’ll Be Seeing You” (the title comes from a favorite 1930s song of Art and Jeanne) begins in 2011 and takes the reader along as Berg, who lives in Chicago, and her sister Vicki in the Twin Cities (whom Berg credits with “doing the heavy lifting”) guided their parents through a difficult transition, along with a brother who lives in Hawaii.

Art, an Army veteran who had prided himself on a disciplined life, was 89, growing forgetful and persistently demanding attention from Jeanne, 88. For his wife’s part, slowly losing the man she loved was upsetting, made even more difficult once it became clear the couple’s living situation needed to change.

“First my mom wanted to move, and then she didn’t. Then my dad wanted to move, and then he didn’t,” recalled Berg. After finally agreeing to the change, it wasn’t long before Berg’s mom became very vocal about how unhappy she was in their new apartment and how she missed the home they lived in for more than 40 years.

Berg acknowledged it was a profoundly emotional time for her mother.

“Her sister Tish died right when [my parents] moved, her husband was deteriorating, and there was a lot put on her,” Berg said, adding that, as her daughter, one of the biggest challenges of the experience was seeing “the emotional devastation” these sad changes were wreaking on her mother.

A Relationship Transformed

In the book, Berg documents how her parents’ relationship was transformed, often in imperfect ways.

“I knew my father was besotted with my mother from the time he met her. She was his North Star,” Berg recalled. “This was amplified so much when he started having trouble, how much he adored her.”

As Berg writes, her mother struggled in her new role:

“The man she combed her hair for and put on lipstick for every night before he came home for so many years. He is so mightily compromised now. She must make the decisions, balance the checkbook, cook, clean, remind him to take his medication, remind him of everything… It’s as though someone wheeled a shiny new ten-speed to her door and said, ‘Hey, you eighty-eight-year-old woman who never learned how to ride a bike! How about hopping up on this one?'”

However, as time went on, there was a softening between the couple, which served as a source of inspiration for Berg. Art reluctantly began participating in an adult day care program, which he eventually enjoyed and which gave Jeanne some much-needed respite.

At the same time, Jeanne acquiesced to Art’s suggestion that they participate in occasional social events at the assisted living facility, and she began to become friendly with some of the residents.

“In the end, what I learned most is how their love endured and how it brought them together even under the circumstances. I would not have predicted this was going to happen, that there would be that kind of accommodation from her,” Berg said.

Art died in 2012, and Jeanne in 2015. Now that time has passed, as Berg writes, she describes the feeling of missing them like “I’ve had a glimpse of something about them that escaped me when they were alive.”

As she recalls in this excerpt from the final pages of the book:

“It might be a memory of something that really happened. For example, after my father died and we were helping my mother clean some things out of the apartment, I came across a flyswatter bedecked with plastic daisies. “Do you want this?” I asked, holding it up.

“Yes,” she said, and took it from me and lay it on the table with great care. “Your father made that for me in daycare.”

She stood looking at it for a moment, then went on with sorting. I stood looking at it, and a thousand things occurred to me about the way that even in bitterness and confusion and anger, my parents’ love for each other endured. I saw that whenever I was looking at them, I was seeing only the tip of the iceberg. They belonged to each other more than they belonged to us.”

Lessons Carried Over to the Pandemic

When asked how she’s coping during the pandemic, Berg says one of the surprising takeaways from writing her parents’ story was how some of the lessons she learned from them are applicable in this uncertain time.

“You’re treading water. You can’t see the horizon,” she said. “You learn to get smaller, to appreciate the smallest things.”

On her Facebook page, which has more than 40,000 followers, Berg recently posted an idea she had to create her own “vision board” and formalize goals to continue to bring joy into her life in the ways she can.

“I’m setting at least an hour a day, if not two, for deep reading. I don’t want to read fluff,” she said. “I want it to mean something to me.”

The same goes for music. On the day of our Zoom interview, Berg had just finished listening to jazz clarinetist Benny Goodman, saying “it made me feel like I was in a Woody Allen movie.”

It’s also a time when she believes we have to rely on ourselves, rather than serendipity. “No invitation is forthcoming, and if it is, you probably shouldn’t go,” she said with a laugh.

However, she has been actively involved in several virtual events promoting “I’ll Be Seeing You,” including archived appearances with A Mighty Blaze, a social media community helping authors connect during quarantine, as well as Friends and Fiction, a collective of five other bestselling authors.

Overall, Berg encourages looking at this time as an opportunity to “come clear in yourself about what the things are that really matter to you. We can all still do so much.”

She shares a favorite quote: “You need someone to love, something to do, and something to look forward to,” she said. “I think that’s the wisest piece of advice.”