By Judith Graham for Next Avenue

Caring for someone with a serious illness stretches people spiritually and emotionally, often beyond what they might have thought possible.

Dr. Arthur Kleinman, a professor of psychiatry and anthropology at Harvard University, calls this “enduring the unendurable” in his recently published book, The Soul of Care: The Moral Education of a Husband and a Doctor.

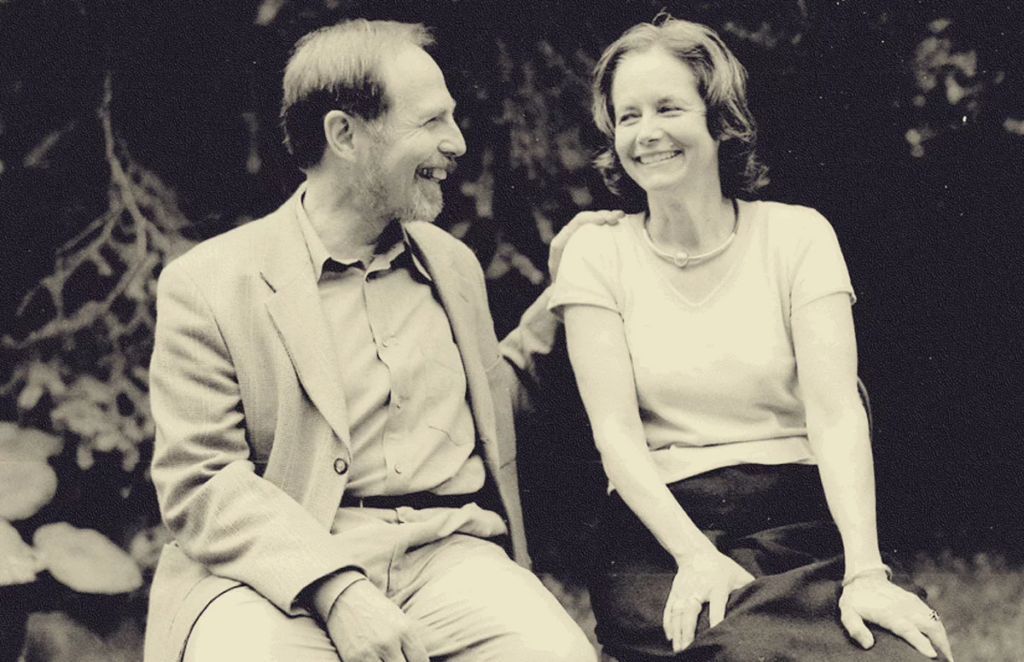

The book describes Kleinman’s awakening to the realities of caregiving when his beloved wife, Joan, was diagnosed with a rare form of early Alzheimer’s disease that causes blindness as well as cognitive deterioration.

Although Kleinman’s specialty is studying how patients experience illness, he wasn’t prepared for the roller coaster of family caregiving. Each time he adapted to Joan’s changing condition, another setback would occur, setting off new crises and fueling uncertainty and stress.

During 11 years of caregiving until Joan’s death in 2011, Kleinman learned that no one who goes through this experience emerges unchanged. He became less self-centered, more compassionate and more aware of how the health care system fails to support family caregivers ― the backbone of the nation’s long-term care system.

Realities of Caregiving

I spoke with Kleinman in mid-November at a caregiving panel. His remarks below are edited for length and clarity.

About his book: “I wrote it for a specific reason. I had spent my whole career as an expert on care. I myself was a psychiatrist who worked with patients with chronic medical disorders, [such as] chronic pain, diabetes, heart disease and cancer. I thought I knew it all. A veil of ignorance was raised from my eyes by my experience as a primary family caregiver.

“What is that veil of ignorance about? It’s about recognizing just how difficult family care is for [people with] dementia and, not just dementia, but many other problems.”

Daily responsibilities: “Let’s say in the fifth year, what was it like? I would get Joan up around 6 a.m. and take her to the bathroom. I have to handle the toilet paper, wash her hands, dress her to work out, take her to the bath and bathe her.

“I would shampoo her hair, dry her, pick out her clothes [for the day]. After that, I would prepare breakfast. As she got increasingly agitated, [that] became difficult because I had to sometimes hold her hands [to] keep her from throwing things or getting up and hurting herself. Because she was blind, she couldn’t see where she was. And then I would help her eat ― usually, at the end, feeding her ― and then take her to a room where we would sit and listen quietly to music.

“Maybe six, seven years into this, I would just sit there and hold her hands. And even that became difficult. So, I would tell her stories of the past … our stories. [Editorial note: This is just the beginning of a day full of similar tasks.]

“I discovered early on that the ritualization of acts of caring ― the dressing, bathing, all these things ― is a way of habit formation that keeps you going.”

Challenging masculinity: “We had a great relationship, but it was asymmetrical. For thirty-six years, my wife took care of me. I was raised as a classical male in the 1940s. When I showed an interest in cooking, my grandmother said to me, ‘What are you, a sissy?’ I was a tough kid on New York [City] streets. I had the most unpromising beginnings to be a caregiver. And my wife slowly socialized me to a different kind of masculinity, to be able to care.

“[Pay family members for caregiving] and you’ll see more men do it. Go to Australia, for example, where there’s very good compensation for care, and you’re astonished at the number of men who are caring for children, who are caring for elderly, and the like.”

Asking for help: “I have a wide circle of friends and colleagues, and [after the book] many of them said they had never realized what was involved. Part of that was my fault. I had a lot of trouble asking for help. Actually, at one point, I so exhausted myself that my kids, who are great, said, ‘You really need assistance.’ And they stepped in, as did my mother, who at the time was in her nineties.

“So, I had a great system of care around me, but I [also] needed a home health aide to [help with Joan and] keep myself going. I found an Irish woman … and she was fabulous.”

Maintaining presence: “In spite of that, I found it extraordinarily difficult in terms of other elements of care, one of which is presence. To keep your liveliness, your love, the presence of who you are going while you’re doing all this work of caregiving ― it is extremely difficult and demanding, but it’s crucial.

“When people ask ‘Why do you do [this]?’ the answer of most family caregivers I’ve spoken to is ‘Well, it was there to do. It’s got to be done, [so] you do it.’”

Learning about failure: “I was fortunate in life; I had a golden career. I have a personality that is like a bulldog, and when I start something, I finish it. But there’s no finishing care. Every one of us [family caregivers], if we’re honest, you fail at a certain point. The frustrations build, anger mounts, you control your anger so you don’t injure the person you’re caring for. But you’ve got to somehow handle it inside you.”

The soul of care: “I think what lies at the soul of care is a form of love. You will do everything you can for another because they mean so much to you. [But] it is also problematic, because we all have complex relationships and we’ve got other things going on in our lives.

“We endure, we learn how to endure, how to keep going. We’re marked, we’re injured, we’re wounded. We’re changed … [in] my case, for the better. If you had known me before my eleven years of care, you wouldn’t recognize me today. I was your classical hard-driving Harvard professor … as tough as any other professor at Harvard Medical School.

“I’ve redeemed myself through this experience, in a way.”

A call for change: “How do we strengthen caregiving? How do we do those things that will make it recognized as important as it is? It’s going to take a radical rethinking. Our health care system [is focused on] entirely the wrong issues. Economics is not the most central aspect of care; it’s caregiving.

“Do you know not a single one of the senior neurologists I went to with Joan who wanted to do everything diagnostically made the recommendation ‘You want to think about a home health aide now, even though you don’t need it right now. You have to look into how you’re going to reconfigure your house [for] someone who’s both blind and with dementia. [Or] a social worker is a great navigator of what the health care system is about. You want to take advantage of that.’

“So, this is where I believe that our whole health care system has got to be rethought, from the bottom up with attention to care at its core.”

(This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News.)

Judith Graham is a contributing writer to Kaiser Health News and Next Avenue.