By Jackson Rainer for Next Avenue

A friend asked with genuine concern, “How are you?”

“I’m OK. Not very happy, never am. I think the world is a pretty crazy place, but I’m OK,” I replied.

“Really? You look troubled. I’m asking because I want to know how you are … really,” she said.

Even with the loving nudge, I said, “Really…I’m fine.”

I was not fine and apparently it was more obvious than I wanted to admit. Now several years after my wife’s death, I am still feeling, with alarming frequency, the cloying sense of loss due to the absence of my “better half” with whom I lived and loved most of my adult life.

Even though I am well trained as a psychologist and have years of my own psychotherapy, I am generally loath to admit this ongoing sense of loneliness to myself, certainly not to anyone else.

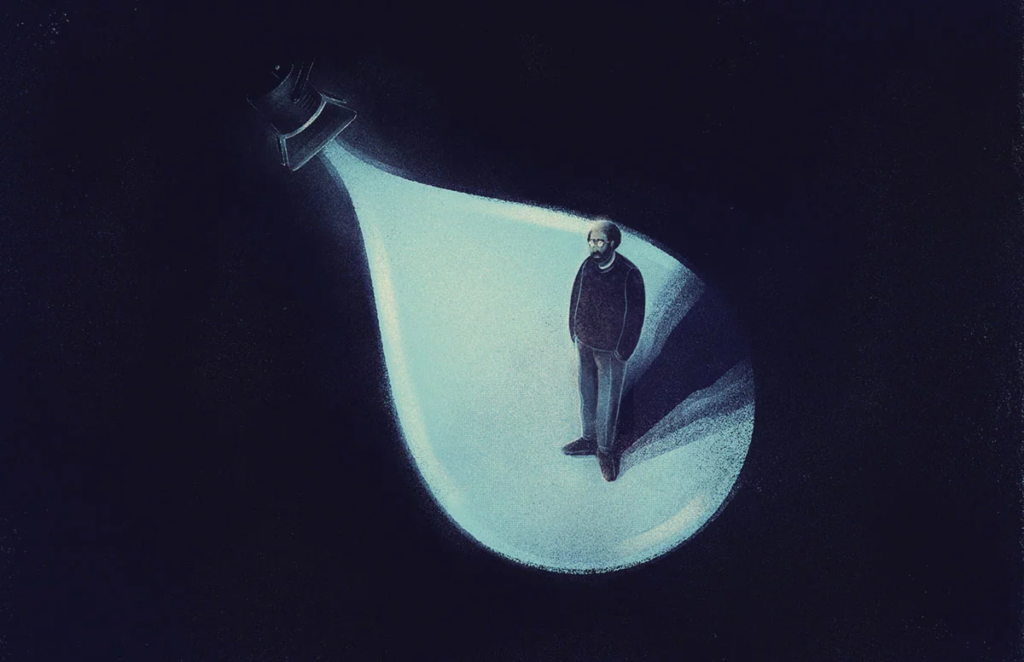

Minutes before my friend’s inquiry, I was giving myself a good talking-to, thinking out loud, “You are just going to have to bear this and live with it. You are in this all alone, big boy. Get used to it.”

Defaulting Into Solitude Rather Than Connection

Understanding the way men grieve has new and deeper meaning for me as a widower. I’ve studied the phenomena as a researcher and clinician for years. Experiencing life after loss is fundamentally different territory from thinking about life after loss. Contemporary theories suggest that men and women express grief along a continuum of styles ranging from those called intuitive, centering on the expression of affect, to those called instrumental, who find physical and cognitive expression more palatable.

Men tend to lean toward the instrumental expression of grief, orienting to emotional control, a disinclination to talk about matters of the heart, to default into solitude rather than connection and to focus on action more than talk. I fall squarely in this masculine camp.

Young boys are socialized in ways that profoundly impact the expression of grief as adult men. Though the social and interpersonal needle has moved toward open expression of feeling as acceptable and desirable, most of us guys hear our Y chromosome rattle when we are asked to put words to heartbreak, confusion, vulnerability and the sense of “free-falling” without intimate support.

We tend to close down opportunities for connection and authentic support while adapting to the world in the absence of our loved one. Stoicism is valued more as a marker of independence and dignity, while vulnerability feels dangerous, weak and ill-advised.

The cultural expectation about what constitutes healthy grieving holds that to heal, a person must speak of, process and “work through” personal thoughts and feelings, sharing them out loud and in the presence of others. In this rubric, the bereaved person adapts to the world in the absence of their loved one by maximizing social support and investing in other relationships and meaningful activities.

However, for many men, the pain of grief is absorbed and processed differently. While the grief experience naturally creates opportunities to turn inward and slow to a more deliberate pace of life, when viewed through a traditional male social lens, this feels threatening, since masculinity typically is equated with striving, moving and activity.

Helpful Road Markers for Healing

So, if it is the case that men typically grieve in a different way than women, how can the experience be processed in a healthy and meaningful way? There are several road markers that are helpful:

Find a safe place to mourn. The Jungian analyst Jerry Wright says, “Go to the place you call holy and weep.” Having one or two confidants who serve as witnesses to another’s grief may enhance the sense of anchoring to the world. Those friends who can listen and be present without judgment are invaluable, particularly when loneliness feels isolating, cold and prickly.

Stay active. Depression is insidious and seductive. Withdrawing from the world leads to a sense of stuckness. As noted, there is value in finding friends who can offer activity, companionship, collegiality and time for reflection. Many men report that sharing vulnerable and tender emotions and thoughts is easier in the context of activity.

Be careful, though. There is one activity that doesn’t particularly heal: work. While throwing yourself into work is distracting, it creates distance from the time and space needed to heal. Certainly, productive activity is necessary and good to make it through the day. But work can be agitating and complicating to the attribution of meaning of the loss.

Know that there is no one way to grieve correctly. Many people hold opinions about “how you’re doing.” Most are loving, but they are like another’s clothes: they may neither fit nor be to your taste. Honest, personally felt acknowledgement of the loss and its day-to-day impact is more relevant, whatever form it takes.

For some, mustering strength and activity is effective. For others, becoming thoughtful and analytical about the death makes sense. For many men, the expression of new or unusual feelings, such as anger or living on the verge of tears, is alarming. The bottom line is found by staring the loss in its face and feeling whatever comes from this profound challenge.

Avoid clichés. Not long ago, an old friend who knows a great deal of my personal path of grief, asked after me. “I’m sitting up and taking nourishment,” I laughed snarkily, while hoping he would leave me alone. Rather than dismissing me or a making a bad attempt to provide a simple solution to my difficult reality, he said, “Let’s go to lunch and visit.” He heard past the funny cliché and invited himself into my world. We had a lovely meal and I was better for being with him.

Make contact with others. Grief teaches a hard lesson. Rather than waiting for others to seek me out, which will not happen (life goes on quickly for everyone except the mourner), I must put one foot in front of the other and find those people in places and events that entertain, satisfy and engage me. Men who mourn will need to tell others how to invite contact. Remember to be prepared with a ‘yes’ to most invitations that come along the way, even when psychic energy is at a premium.

Be aware of holidays. Holidays and personally significant days provide psychological punctuation to our lives. Such days emphasize our loved one’s absence and bring corresponding pain. Holidays are oriented to family, tradition, continuity and familiarity. Recognizing that such days will unfold differently because of the loss will give a bit of perspective while still honoring the loved one’s death.

Watch for warning signs. Because many men are prone to run and hide from the experience of grief, real problems may emerge. The warning signs warranting careful attention are:

- Depression lasting longer than two weeks or withdrawal from activities of daily living

- Deterioration in family and friends’ relationships

- Physical complaints, such as headaches, fatigue and low back pain

- Chronic anxiety, agitation and restlessness, characterized by ruminations, obsessions or insomnia

- Alcohol or drug abuse or dependence

- Indifference toward others, insensitivity and workaholism

Additional Next Avenue Stories About Men and Grief

Over the past several months, we’ve featured several stories by, and about, men on the topic of grief. Two are about fathers mourning the loss of their twentysomething sons; one is about author Jonathan Santlofer’s sudden plunge into widowhood and another is by the author of this piece, Jackson Rainer, on the second year after his wife’s death. There is also a piece on how men deal with the death of a friend.

Here are the links to those stories. Next Avenue is committed to continuing to tell stories of grief since all of us, at some point in our lives, will experience this complicated emotion.

- “Finding Meaning in Grief”

- “A Father’s Grief: When Love Isn’t Enough”

- “Author Jonathan Santlofer Reflects on Grief”

- “The Second Year After a Loved One’s Death”

- “When Your Best Friend Dies”

Part of the IN GOOD COMPANY SPECIAL REPORT

Jackson Rainer is a board certified clinical psychologist who practices psychotherapy with individuals and couples at the Care and Counseling Center, Atlanta. He is a Professor Emeritus of Psychology with the University System of Georgia.