By Richard Harris for Next Avenue

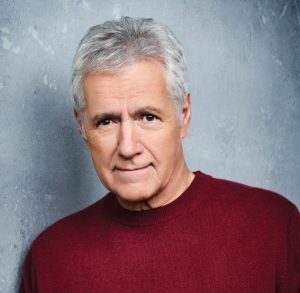

Alex Trebek: The Answer is… Reflections on My Life is not your typical autobiography or standard memoir. Rather, it’s what the 79-year-old Jeopardy! host calls “a series of quick look-ins, revelations.”

Trebek has been a public figure for most of his professional life. But since he moved to Southern California from Canada in 1973, he has not lived the “see and be seen” Hollywood celebrity life.

Late last year, Trebek openly questioned whether he should have disclosed that he was diagnosed with Stage IV pancreatic cancer in March 2019. “There are moments when I regret going public with it, because there’s a little too much of Alex out there right now. It does place a responsibility on me that I feel I’m not deserving of,” he said.

Trebek last recorded fresh episodes of Jeopardy! in March when the pandemic shut down production. Still in treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer, he managed to record show opens a few weeks ago at his home for some special Jeopardy! broadcasts airing this month and next. But because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, there’s no telling when tapings for the 37th season of Jeopardy! will begin.

The New York Times reported that if the current course of his cancer treatment fails, Trebek plans to stop treatment. “There comes a time when you have to make a decision as to whether you want to continue with such a low quality of life, or whether you want to just ease yourself into the next level. It doesn’t bother me in the least,” he said.

The following are excerpts from Trebek’s new book:

On Why He’s Never Written an Autobiography or Memoir Until Now

My life was not particularly exciting. I’m the typical product of my generation: a hardworking breadwinner who looks after his family; does all the repairs he can around the house; enjoys watching television and thinks a simple dinner of fried chicken, broccoli and rice is just fine, thank you very much.

I’ve shown up to work at the same job for thirty-six years and have lived in the same house for thirty years. I respect and like my colleagues, and have a family that I dearly love. I have never seen myself as anything special. That’s why if you listen to Johnny Gilbert’s announcement at the opening of Jeopardy!, I’m introduced as “the host” rather than “the star.” I insisted on that when I took the job back in 1984. But then early in 2019, all of that changed when I was diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer.

On Toughness Following His Pancreatic Cancer Diagnosis

I have become in many ways the de facto spokesperson for pancreatic cancer; there are a lot of expectations. I feel a lot of pressure to always be tough — to be stoic and show a stiff upper lip. But I’m a goddamn wuss. I start to cry for no reason at all. I have no idea what sets it off, and it embarrasses me. The thought that I don’t measure up compared to people’s expectations is difficult.

I have become in many ways the de facto spokesperson for pancreatic cancer; there are a lot of expectations. I feel a lot of pressure to always be tough — to be stoic and show a stiff upper lip. But I’m a goddamn wuss. I start to cry for no reason at all. I have no idea what sets it off, and it embarrasses me. The thought that I don’t measure up compared to people’s expectations is difficult.

Not long ago, when I was going through a significant bout of depression, I called my doctor and expressed my concern about not being strong enough. “No, no, no,” he said, trying to reassure me. “You’re a great survivor. You’ve helped a lot of people. You don’t know how many people whose lives you have saved just by being out there, speaking out about the disease, what it does to you and how to maintain a more positive attitude.”

Interestingly, the longer I’ve lived with the cancer, the more my definition of toughness has changed. I used to think not crying meant you were tough. Now I think crying means you’re tough. It means you’re strong enough to be honest and vulnerable. It means you’re not pretending.

And not pretending, being willing to let your guard down and show people how you truly feel and admit that you’re a wuss, is one of the toughest things a person can do. It’s also one of the most helpful things a person can do. It demonstrates an interest in developing an understanding. It demonstrates a caring. Because you have to figure there are some people out there who are going through the same stuff.

On the Will to Survive

I don’t think the will to survive is a constant. I think there are moments — and there are certainly moments in my life — when that will to survive disappears and I’m ready to pack it in.

Because understand that death is part of life. And I’ve lived a long life.

If I were in my twenties with years ahead of me, I might feel differently. But when you’re about to turn eighty, it’s not like you’re missing out on a great many things.

I don’t have much stamina anymore. It’s not even a question of physical activity that tires me out. Just being awake is enough to exhaust me. Some days are better than others. I had a couple of good days, then yesterday didn’t go so well. Today is fair. Just pain and fatigue and, well, different kinds of agony. Each day brings a new set of challenges.

I don’t like to use the terms “battling” or “fighting” when talking about cancer. It suggests that there are only two outcomes: “winning” and “losing.”

That’s nonsense. I understand why we human beings choose to see cancer in these terms. It’s easier to comprehend and less scary if we see the experience as a boxing match and the disease as an opponent who might be subdued by sheer force of will and determination.

However, cancer doesn’t get demoralized. It doesn’t require a pep talk from its trainer between rounds. It is a fight, that’s true.

There are days when I feel like Mike Tyson just dropped to the canvas by a Buster Douglas uppercut.

But it is by no means a fair fight. Not even close. It is simple biology. You get treatment and you get better. Or you don’t. And neither outcome is an indication of your strength as a person. Yet I still believe in the will to live. I believe in positivity. I believe in optimism. I believe in hope, and I certainly believe in the power of prayer.

On Retirement

For years, studio audiences have asked me, “Have you ever thought about retiring?” And I’ll respond, “Yes, I’ve thought about it. Why? Do you know something I don’t?” Or they’ll ask, “How do you motivate yourself to do the same job year after year?”

And I’ll respond, “They pay me very well.”

One of the elements of my personality has always been — and I’m keenly aware of this — that if something was that important to me, that much of a driving force, then I would do something about it. The fact that I have not done something about changing my job is an indication that maybe I’m pretty satisfied, pretty content with where I am.

It’s not hard to be content with being the thirty-six-year host of Jeopardy! You get a lot of respect. And, as I’ve discovered since the diagnosis revelation, you get a lot of love. There really is no downside to it. It’s not like I trudge to work every week and say, “Oh gosh, I’ve gotta do Jeopardy! again.” It invigorates me.

No matter how I feel before the show, when I get out there it’s all forgotten because there’s a show to be done. Yet I know there will come a time when I won’t be able to answer that bell. I know there will come a time when I can no longer do my job as host — do it as well as the job demands, as well as I demand. Part of it is physical. Standing on your feet for eleven hours two days in a row is difficult for someone who’s about to turn eighty, even without getting worn down by chemotherapy.

My eyesight has also deteriorated over the years. It’s not as easy for me to read the clues. The chemo has caused sores inside my mouth that make it difficult for me to enunciate. One treatment also turned my skin dark brown, and the chemo, of course, caused my hair to fall out. But part of it is mental too. I’m the first to admit I’m not as sharp as I once was. I have more and more brain skips. What I call “senior moments.”

And in this job, concentration is imperative. You can have those slip ups in casual conversation with friends. But you can’t get away with that as the host of Jeopardy! Whenever it gets to that point, I’ll walk away. And Jeopardy! will be just fine. There are other hosts out there who can do equally as good a job as me. I think Jeopardy! can go on forever.

On Getting Your Affairs in Order — and Death

I keep reading about people who have different kinds of cancer, and they see their doctor and say, “Well, what’s the prognosis?” And the doctor says, “I think you better get your affairs in order.”

My doctor has not said that to me. He has told me he is there for me, no matter what my decision is. There are different decisions, of course. I could decide to begin a new chemotherapy protocol. I could decide to try a new immunotherapy. Or I could decide to go to hospice. The other day, I talked to my doctor for the very first time about this last option. He explained that hospice is basically there to make you comfortable on your way to the end. They’re not there to administer health care, but palliative care.

But when death happens, it happens. Why should I be afraid of it? Now, if it involves physical suffering, I might be afraid of that. But, according to my doctor, that’s what hospice is for. They want to make it as easy as it can possibly be for you to transition into whatever future you happen to believe in.

Am I a believer? Well, I believe we are all part of the Great Soul — what some call God. We are God, and God is us.

Lately, I’ve been thinking more and more about that old line they used to use in the military: “No one’s an atheist in a foxhole.” If ever there was an opportunity to believe in God — a god — this might be a good one, Trebek, now that you’re on the verge. What have you got to lose?

On Life

My life has been a quest for knowledge and understanding, and I’m nowhere near having achieved that. And it doesn’t bother me in the least. I will die without having come up with the answer to many things in life. I’m often asked how I would like to be remembered. I don’t think about it much.

But I suppose if I had to answer I would say I’d like to be remembered first of all as a good and loving husband and father, and also as a decent man who did his best to help people perform at their best. Because that was my job. That is what a host is supposed to do.

You are there to make the contestants relax enough that they can demonstrate their skills. They are the stars of the show. They are the ones the viewers tuned in to see. And if you do that, if you put the focus on the players rather than on yourself, the viewers will look on you as a good guy. If that’s the way I’m remembered, I’m perfectly happy with that.

With the coronavirus, [our family] can’t go out to eat, we can’t go out to public places, even the park next door has limited its use. Here I am wanting to enjoy what might be the last of my days, and, what, I’m supposed to just stay at home and sit in a chair and stare into space? Actually, that doesn’t sound too bad.

With the coronavirus, [our family] can’t go out to eat, we can’t go out to public places, even the park next door has limited its use. Here I am wanting to enjoy what might be the last of my days, and, what, I’m supposed to just stay at home and sit in a chair and stare into space? Actually, that doesn’t sound too bad.

Except instead of a chair, I’ll sit on the swing out in the yard. That’s my favorite spot on the whole property. I used to do it with Mom. Just sit there and rock. No need to talk.

It’s just very peaceful. I suppose the feeling I have sitting on that porch swing is similar to what people feel when they meditate, though I would never call it meditating. I just consider it goofing off, not doing anything.

Yep, I’ll be perfectly content if that’s how my story ends: sitting on the swing with the woman I love, my soul mate, and our two wonderful children nearby. I’ll sit there for a while and then maybe the four of us will go for a walk, each day trying to walk a little farther than the last. We’ll take things one step at a time, one day at a time.

In fact, I think I’ll go sit in the swing for a bit right now. The weather is beautiful — the sun is shining into a mild, mild looking sky, and there’s not a cloud in sight.

(Editor’s Note: For more on Alex Trebek and Jeopardy!,

read this interview with Lisa Rogak, author of Who is Alex Trebek?, “The Answer Is…A Biography of Alex Trebek.”)

Richard Harris is a freelance writer, consultant to the nonprofit iCivics and former senior producer of ABC News NIGHTLINE with Ted Koppel.