By Kevyn Burger for Next Avenue

The six-decade love story between Eleanor and Peter Baker began when they spotted each other at the candy counter at Woolworth’s in Rutherford, N.J.

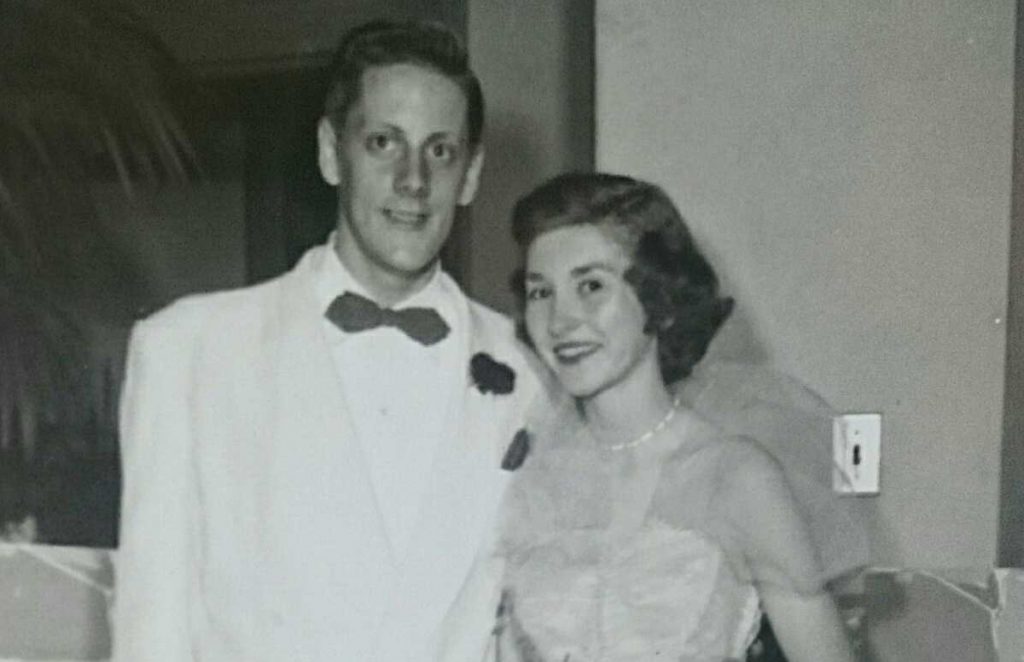

They went on to be prom dates (pictured above), bride and groom, parents, grandparents and great grandparents. They were living their retirement dream, traveling between the Poconos in Pennsylvania and their winter home in Florida when they attended a March 10 reunion with Peter’s fellow retired New Jersey State troopers and their wives who were also spending their sunset years in the Sunshine State.

It was there that the couple was exposed to the coronavirus.

In April, Eleanor, 84, with her husband at her side in a Florida hospital room, died of COVID-19; Peter, 85, passed away from the virus within 24 hours.

“We’re reeling. It’s like the floor dropped out from under us,” said Patty Wolfe, 61, the eldest of their five children. “We didn’t expect people who were relatively healthy to be brought down by a virus. They were the nucleus of our family.”

A Toll on the Silent Generation

The Bakers were members of what demographers have called Traditionalists, Matures and, most commonly, the Silent Generation. Wedged between two larger and more well-known groups — the Greatest Generation and the boomers — members of the Silent Generation were born between 1929 and 1945, marked by the start of the Great Depression and the end of World War II.

Now the coronavirus is taking a cruel and disproportionate toll on these resilient Americans, born into hard times and raised to do their duty for the greater good.

“Many of them should still be with us. They had not reached the natural end of their lives. The sheer number of these deaths in such a compressed amount of time is hard to fathom,” said Katie Smith Sloan, president and CEO of LeadingAge, the association of nonprofit providers of aging services.

As casualties accumulate at an alarming pace, there’s been no fond valedictory for this group that helped lift their country to its postwar prosperity.

“These are the people who built our communities and our country. As a generation, they sacrificed so much. We are losing their wisdom and life experiences when we still have so much to learn from them,” Sloan said.

Marked and Shaped by Momentous Events

Now between the ages of 75 and 91, the Census Bureau counts 23 million members of the Silent Generation. There are but 2.5 million survivors of the Greatest Generation, who are 92 and older, and 76 million boomers, between 53 and 74.

Like every generation, the members of the Silent Generation were marked and shaped by the momentous events of their coming-of-age years.

“The Silent Generation grew up to be responsible and not put their own needs first. When they were kids, they were expected to do as they were told and stay out of the way of adults,” said Ann Fishman, president of Generational Targeted Marketing.

Many of the Silent Generation remember listening to the attack on Pearl Harbor as children, in the same the way that their youthful millennial grandchildren watched the searing scenes of 9/11.

Their fathers and older brothers marched off to war and their mothers went to work in aircraft factories while they did their part for the war effort, tending Victory gardens and using ration coupons for necessities.

A far smaller percentage of Silent Generation men were drafted and served during the Korean Conflict, but the culture of the military, so prominent in their childhood, shaped them to respect authority. As parents and workers, they understood a top-down, command-and-control hierarchy.

“Their role models were people larger than life — Patton, Eisenhower. You didn’t challenge them. They were rewarded for playing by the rules,” Fishman said.

The Lucky Few

The ‘Silent Generation’ term was coined by Time magazine, in a 1951 cover story about the post- World War II generation.

Elwood Carlson prefers to call them the Lucky Few, which is the title of the 2008 book he wrote about them.

“They were the first American generation that was smaller than the previous one. The birth rate went really low and stayed low in the Great Depression. A lot of people hit the hardest did not have families. Many men were not with their families, they were unemployed and roaming, looking for work. Couples postponed having children,” said Carlson, who is the Charles Nam Professor in Sociology of Population at Florida State University.

That explains the few. But why does he consider them lucky?

“It was tough when they were born, but by the time they got out of school, they got on the gravy train. They became adults during the longest continuous economic boom in U.S. history,” Carlson said. “They founded, or were on the ground floor of, many new corporations. As the economy was going crazy, there was a shortage of people because of that low birth rate, so they got jobs, promotions and raises. Their unemployment rate was half what it was for the boomers a generation later.”

Carlson notes that African Americans of the Silent Generation did not benefit from the nation’s economic success in the same way their white counterparts did, but the rising tide also lifted many people of color. Often, they were children in the era of the so-called Great Migration, when African Americans left the rural south to relocate to better opportunities in the urban northeast, midwest and west.

“They were subjected to racist institutions, but they didn’t lag as much as the generations before them in terms of employment and income,” Carlson said.

Now, in the midst of the pandemic, Carlson wonders if the good luck of the Lucky Few has run out.

“They’ve finally rolled snake eyes. Some people are saying they should be sacrificed to the economy when they built the economy,” he said. “They are now perceived as collateral damage. It’s a shame.”

A Silent President?

Members of the Silent Generation have left large footprints across every sector of society and many of them continue to exert a powerful influence even today.

Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Stephen Breyer, born in 1933 and 1938, are of the generation, as are Rep. Nancy Pelosi and Sen. Bernie Sanders.

All of The Beatles and three of the four surviving Rolling Stones (Ron Wood is just barely a boomer) are Silents, as are Dr. Anthony Fauci, Pope Francis, Gloria Steinem, Tina Turner, Dustin Hoffman, Julie Andrews and Warren Buffett. Now deceased generational influencers include Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Elvis Presley.

But there has never been a U.S. President from the cohort. The nation skipped from Greatest Generation chief executives — Kennedy, Nixon, Carter, Reagan and George H.W. Bush — to boomers, including Clinton, George W. Bush, Obama and Trump.

Should Joe Biden, born in 1942, move into The White House, he will be the first, and logically, the only, Silent Generation member to assume the highest office.

“Unlike the G.I. Generation, they could only imagine the feeling of saving the world. They never experienced that. They are the helpers, not the decision-makers,” explained Fishman.

“Their role has been to humanize their world. They started the civil rights movement and the women’s movement. They are problem solvers, mediators, commentators. Every president since Kennedy has had one of them as their chief of staff or vice president,” she added.

Throughout their long lives, they have retained their power over the purse strings. According to the Federal Reserve, Americans over 70 (mostly Silent Generation members) still control 28% of the nation’s household wealth.

“They are financially stable and wise,” Fishman said. “As children of the Depression, they have never been wild spenders, so they have money. They’ve always made the best and the most of what they have and now they like to help their families.”

Gone Too Soon

Eleanor and Peter Baker personified many of the characteristics associated with their generation. They married young, devoted their efforts to their family and embodied the values embedded in their youth.

“My parents were extremely frugal. They never cut corners and they did things right. Dad was a tinkerer and the best bargainer out there. He kept user manuals, records and receipts. When a blade broke off their ceiling fan, he found a receipt from eighteen years ago and took it back,” recalled his daughter Patty Wolfe.

Peter rose to be a captain in the New Jersey State Police while Eleanor was, in Wolfe’s words, a “legendary homemaker” who drove a school bus for some years around raising her children.

The loss of “Gammy and Pop-pop,” as their great-grandchildren called them, was particularly poignant over the Fourth of July, when the couple traditionally hosted an intergenerational family get-together of 65 or so.

“Our family is spread all over the place, but they always brought us together,” Wolfe said.

In recent years, Peter had slowed down because of his Parkinson’s diagnosis, but Eleanor had recently undergone knee replacement surgery to keep active and traveled to Europe with another daughter within the past year.

“I’m glad they were together at the end; maybe that brings us solace,” Wolfe said. “But they weren’t ready to go. They had plans. Next year is the hundredth anniversary of the State Police and they were planning to be with the group recognized at the Army-Navy game at Giants Stadium. They had a lot of living yet to do. The virus took them from us.”

Kevyn Burger is a freelance feature writer and broadcast producer. She was named a 2018 Journalist in Aging Fellow by the Gerontological Society of America. Based in Minneapolis, Kevyn is the mother of three young adults and one rescue terrier.