By Mary Kay Jordan Fleming for Next Avenue

For years, I’ve feared my 70-member family was coming apart at the seams. Marriages, relocations, and deaths loosened the bonds my parents stitched together a lifetime ago. Holiday potlucks in a rented clubhouse replaced regular Sunday dinners in someone’s home.

Several years ago, when the clubhouse was unavailable, our communal Thanksgiving meal splintered into smaller family groups, and in 2020, the pandemic cancelled every holiday gathering.

I worried about leaving my two children a family smaller and more scattered, emotionally and geographically, than the one that anchored me. As a member of the oldest generation in my family and the youngest of five siblings, four of whom are still living, I wondered who would carry on family traditions. Who would teach the next generations about the grandparents and great-grandparents who loved them into existence?

Beginning A Family Project

More than a decade ago, I launched an annual newsletter to keep our extended family in touch. But emails and newsletters were a poor substitute for togetherness. My brother Bill suggested I update a family cookbook our niece Jeanie made on a word processor several decades ago.

“I still use that booklet,” he said, “but it’s getting old. There is a new generation who could contribute.”

He pitched the idea as a cut-and-paste operation not so different from the newsletter. But I foresaw months of retyping, editing and formatting. And for what? A bound collection that may not compete with 5-star recipes available online? Why bother, I wondered.

Then I stumbled on heirloom-style cookbooks that featured family lore and photos, and recognized myself as clearly as if looking into a mirror. I have always recorded loved ones’ names with treasured recipes: Mom’s butter cookies, Dad’s chili, Jeanie’s chicken stew. Without those names, I’d forfeit my favorite part of cooking — renewing my connection with the person who loved me enough to cook for me.

When I want stuffed mushrooms, I don’t search online. I reach for the card bearing my late brother’s name so I can remember his wicked sense of humor and picture him in the frilly bib apron he donned every holiday. I’ll never find that on the internet.

Each Message Was a Gift

I reimagined what a new cookbook could be and put it to a family vote: Was anyone interested in updating our original version? If so, did they prefer a simple collection of recipes or a more extensive, and expensive, keepsake volume that included memories and color photos?

The email replies poured in: Yes, yes, it’s time for this! I still use the old one, and Thanks for always being willing to pull family projects together. The vote was unanimous. My big family was hungry for more than food. I was all in.

For two months after my initial ask, relatives ages two to 82 submitted more than 120 recipes, 90 photos, and an equal number of stories.

In any other situation, I would have been exhausted by my overstuffed inbox, but in this case, I couldn’t wait to devour the precious gift in each message: This Apple crumb pie is my Dad’s favorite birthday dessert; It was never Easter until Nana Pat made her famous Sherbet roll and I still make mashed potatoes with a hand masher because I loved the lumps in my uncle’s version.

Several recipes celebrated the cultural traditions of our in-law families.

My late brother-in-law savored the “smell of my home in Beirut” when stuffing red peppers with rice and lamb seasoned with cinnamon, allspice, and garlic. Jeanie’s daughter described her aunt’s speed in hand-forming and frying lagaymot, a honey-rich dessert for Ramadan. My daughter-in-law described learning to cook soul food beside her grandma, whose recipes were never written down. My nephew’s wife reminisced about her abuela’s warm tortillas and fragrant red chile pork.

My oldest sister Mary Ann surprised me with photos of Mom’s old Hoosier cabinet, still in use. In the years before built-in cabinets and large countertops, this freestanding wood furniture housed everything from staple foods and saucepans to utensils and tablecloths. A metal shelf in the center pulled out for preparing pastries.

“I remember all the goodies Mom made on that shelf. I smelled chocolate chip cookies cooling on the windowsill as I walked home from school,” she wrote. “Only two chips per cookie in those days.”

A Cookbook No One Else Could Write

I filled in some of the later history. Unlike the oldest siblings who had a stay-at-home mom, I had the mom who returned to hospital nursing and the dad who retired. Dad took up cooking with gusto, perfecting recipes for chili, bean soup and beef stew. I walked home for lunch in seventh and eighth grades to find him making my favorite tomato soup — always with milk, not water — and grilled cheese every day, just for the two of us.

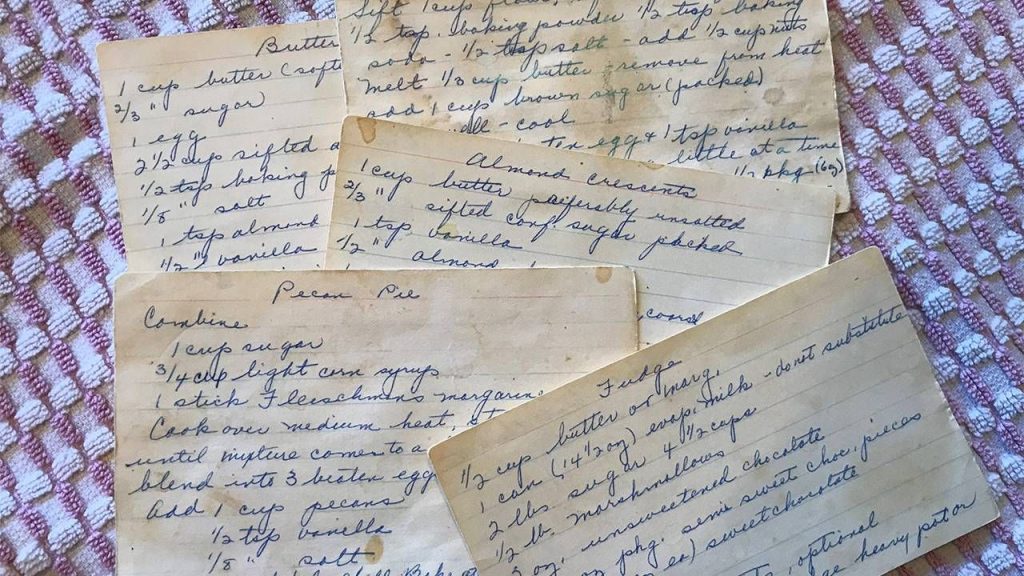

I included photos of Mom’s 1950s “Better Homes and Gardens Cookbook” now missing its cover, Dad’s 1970s “Joy of Cooking” with its spine of blue duct tape and their frayed and food-stained recipe cards. For 45 years since their deaths, I have preserved those cards, relishing the opportunity to revisit their distinctive cursive script, to cradle in my hands the cards they held in theirs and to recreate the aromas and flavors that conjure our lives together.

Bill submitted Dad’s recipe for Old English bread pudding, but conceded, “Somehow mine never smells or tastes quite as good as his.”

Although most of my family enjoys cooking and baking, the cookbook did not overlook our non-cooking relatives.

My beloved late aunt, who wore her “inability to boil water” as a badge of honor, was remembered for two recipes — fried chicken (“Call Mary Beth for a ride to the fast-food chicken place down the street”) and toaster pastries (“Remove pastries from toaster when the kitchen fills with smoke”).

After months of editing, formatting, getting estimates from local printers and spiral-binding our 90-page cookbook, the project I feared as tedious became a blessing. It strengthened my sense of belonging to something larger at the very time the pandemic shrunk my world.

Together, we wrote the book no one else could write — love letters to our next generation — a legacy of devotion that Bill’s son once described as “fierce.”

On receiving her copy of the new book, Jeanie made plans to share it with her growing family.

“My kids never met my grandpa, but they know him through his cheesecake and chili. They know he brushed aside gender stereotypes of his generation and cooked for his family, and his recipes were treasured enough to be passed through five generations,” she said. “One day, my grandson will make that cheesecake and tell his children about my grandpa. That’s immortality.”

My sister Reet called to thank me the day she received her copy. She spent the morning weeping over the photos of beloved relatives, family homesteads and holiday stories. “I’m so surprised! This cookbook isn’t really about the recipes, is it?” Reet asked.

I smiled. “It never was.”

Mary Kay Jordan Fleming is a developmental psychologist and award-winning humor writer [winner, 2016 Erma Bombeck Humor Writing Contest] and first-place winner in the 2019 National Society of Newspaper Columnists humor writing contest for online, blog and multimedia columns (over 50,000 monthly unique visitors).